Tom Taylor and Laura Barker honoured with blue plaque

Jeanne Rathbone

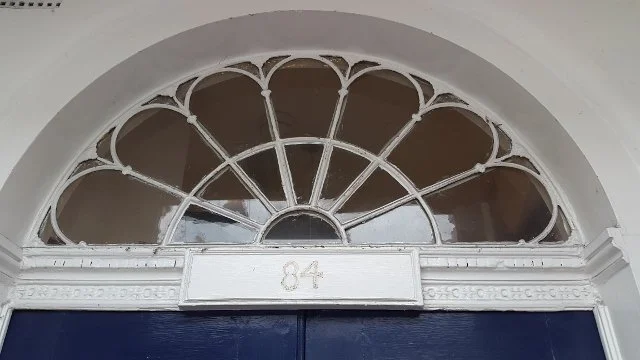

Plaque unveiled at 84 Lavender Sweep

The Battersea Society will unveil a plaque honouring Tom Taylor and Laura Barker on 28 September at 84 Lavender Sweep. This is the site of their home, demolished when Tom died. Tom Taylor (1817-1880) civil servant and playwright and Laura Barker (1819-1905) composer, entertained eminent Victorians at their famous Sunday musical soirées. They have featured in a Battersea Society talk I did entitled Four 18th Century Houses and their Occupants, the houses being located near Clapham Common and Lavender Hill.

Lavender Sweep House with the fanlight now at number 84

Four other villas within their grounds on Lavender Sweep were also swept away, replaced by terraced housing. The speed with which this happened seems quite amazing now, all of it done without the help of cranes or modern building methods. An actor/writer friend John Coleman came to visit the house after Tom had died and found “not a stone remains … and the demon jerry-builder reigns triumphant.” Our own home is opposite the double-fronted number 84, which has the fanlight from the original Lavender Sweep house. It is now a Wandle Housing Association property and they were delighted when permission was sought for a plaque.

84 Lavender Sweep with the original fanlight from Lavender Sweep House

Tom was best known as a journalist, editor of Punch, art critic and the playwright whose play Our American Cousin was being watched by Abraham Lincoln when he was assassinated. Laura, his wife, was a musician, playing both violin and piano as well as composing. However, she did not work as a composer or play professionally after she was married. Sadly, most Victorian middle and upper class women did not continue their careers after they were married due to societal and patriarchal attitudes.

Early years and education

Tom Taylor was born at Bishopwearmouth, a suburb of Sunderland. His father Thomas became head partner in a flourishing brewery firm at Durham, and was selected as one of the first aldermen in the new municipality. Tom’s mother Maria was of German origin.

Tom was educated at Grange school in Sunderland, and afterwards at the university of Glasgow, where he won three gold medals. In 1837, he entered Trinity College, Cambridge and graduated in 1840 with a B.A. in mathematics and classics. He gained an M.A. in 1843. He declined the ample annual allowance hitherto placed at his command by his father, and resolved to support himself on his fees as tutor and the income of his fellowship.

The Old Stagers

During 1842, Taylor, together with Cambridge friends Frederick Ponsonby (later Earl of Bessborough), Charles Taylor and William Bolland, formed the Old Stagers, which is recognised as the oldest amateur drama society still performing. It came after a cricket festival in Kent when Ponsonby was asked to combine cricket and drama in the evening. He rallied around him a group of amateur actors who took to playing cricket with fervour during the day, rehearsing any spare moment they could find on a free corner of the playing field, for their performance in the evening. The Old Stagers latest production, their 171st , was ART by Yasmina Reza, translated by Christopher Hampton, in August of this year at The Malthouse Canterbury.

Tom Taylor and the Old Stagers

Tom’s Career

Tom left Cambridge in 1845 and was appointed professor of English Literature and Language for London University. He held the post for two years after which he practiced law, having been called to the bar at Middle Temple in 1846 and went on the northern circuit. In 1850 he became assistant secretary of the Board of Health. The board was reconstituted in 1854 in response to the cholera epidemic that was ravaging London and he was made secretary, a post he held until 1858, when the board was disbanded. He then transferred to a department of the Home Office, from which he retired in 1876. Apparently, he often walked from Lavender Sweep to work at Whitehall.

While working as a civil servant, he maintained separate careers as a playwright, art critic and journalist, most prominently as a contributor to, and eventually editor of, Punch. He became best known as a playwright, with up to 100 plays staged during his career. Many were adaptations of French plays; on some plays he collaborated with Charles Reade. Whether adaptations or originals, his works ranged from farce to melodrama.

In 1881, after his death, John Oldcastle published an appreciation of him and his wife Laura Barker in The Magazine of Art:“Tom Taylor was an active citizen, a model husband and father, and a faithful friend. In politics he was always a Liberal. Of his home-life little need be said, except that in his wife he had as true a help-mate as ever a literary man had, Mrs. Tom Taylor being one of a family of sisters whom we have heard spoken of as resembling the Brontes in the seclusion of their early life and in the gifts with which they were endowed; and like the Misses Bronte, the Misses Barker were the daughters of a Yorkshire clergyman. It was thus Tom Taylor’s fortune to have a wife--herself a handler of the brush —who aided and seconded his artistic taste, and who in music, as a composer, has great ability. She has published many of her compositions, and she contributed an original overture and entr’acte music to her husband’s “Joan of Arc.”

As a friend, Tom Taylor was beloved and knew intimately most of the “men of the time.” He is buried in Brompton Cemetery.

A woman’s talent constrained by social norms

Laura Wilson Barker was established as a musician and composer by the time she met and married Tom Taylor and they came to live in Lavender Sweep, residing there from 1858 until he died in 1880. She was born on 6th March 1819 in Thirkleby, Yorkshire, the sixth daughter of Vicar Thomas Barker, an amateur musician and painter, and his wife Jane Flower. She was an excellent water colourist as were her sisters. They were all very talented in several artistic directions and were called “the phenomenons” by their contemporaries. Some of her watercolours are on display in Ellen Terry’s home Smallhythe Place.

Laura received her first musical instruction in violin and piano from her parents and then studied composition and presumably also piano privately with the composer and pianist Philip Cipriani Potter, who taught piano at the Royal Academy of Music in London from 1822 and 1832 and became its principal in 1832, remaining in the post until 1859.

Her Seven Romances for Voice and Guitar was published in 1837, followed by an album of six songs for a voice and piano. Many of her compositions are based on texts by Tennyson. Laura’s compositions were received enthusiastically by the public and the press; her services as a musician were much sought after in Leeds and London.

Laura Barker's portrait of Ellen Tracy

As a teenager, Laura Barker encountered numerous musicians in her parents’ home, including Niccolò Paganini, with whom Laura played, aged thirteen. She mentions visiting with his little son Achillino at her uncle General Perronet Thompson’s house in Hampstead. It was this uncle who presented her with a Stradivarius violin.

She recalled of her duet with Paganini, “I played the pianoforte and he the violin. He laughed heartily to hear my imitations of some of his extraordinary feats on the violin.” He said he was much astonished at her power in rendering entirely from ear his wonderful harmonies upon her violin.

In 1836, her father sent one of her compositions to Louis Spohr, a violinist, conductor and composer. She played for him and Laura recalled that Spohr was always very interested in her Stradivarius, helped her with her markings on it and “He was always ready to help me with my violin, and kindly chose a bow for me.” He even suggested her coming to Kassel as his pupil but this never happened.

There is an anecdote about the violin and a visit by Joseph Joachim with his famous prima donna wife Amelie. The contralto was singing when a servant announced there was fire at the top of the house. Laura wouldn’t interrupt the singer but Joachim grabbed the violin and took it out to his carriage declaring, “Whatever else happens, the Strad must be saved.” Laura’s violin was later bought by Tom and owned by the virtuoso Joshua Bell but it was named the Tom Taylor Stradivarius!

She taught music at the York School for the Blind probably from 1843 till she was married in 1955. Once Laura was married, conventions required that she became a middle class wife, a talented amateur perhaps, but not one to be regarded seriously by the art world or to have a career as a composer. Although she did, of course, write accompanying music for Tom’s plays.

I found this cameo in Sir Leslie Ward’s caricaturist known as Spy: “Mrs. Tom Taylor was descended from Wycliffe…, Laura Barker was brought up in circumstances very similar to the Brontës. She was extremely talented, and began her musical career at the age of thirteen and became the composer of many popular songs. When she married she continued to publish her talented songs under her maiden name.”

When Tom died in July 1880, Laura moved with her daughter and two servants to Porch House in Coleshill, Berkshire. She did publish when widowed. A reviewer in 1899 said she was “an amateur of far more than ordinary ability.” That house is now lived in by their great, great grandson Peter Helps.

Lavender Sweep House

The distinctive crescent layout was the creation of Peter James Bennett, a developer of the 1780s with five rus-in-urbe villas. Lavender Sweep House, as it became known, started off high and compact, of three storeys, with a full-height bow on the shorter south front. The longer west front overlooked the grounds, and a short drive from Lavender Sweep led to the main entrance on the east front; a stable and coach-house stood close by on the north boundary.

A later addition was a the three-storey north wing, and extended drawing room, which now opened into a shallow conservatory running along the rear of the house, supported on an iron colonnade.

Taylor added a large study “to his own design.” A visitor in the 1870s found every wall in the house, even in the bathrooms, covered with pictures; a pet owl perched on a bust of Minerva; and a dining room “where Lambeth Faience and Venetian glass abound.”

Lavender Sweep House from the garden

In the circle of eminient Victorians

Tom and Laura held regular Sunday soirees. Visitors included Guiseppe Mazzini, William Thackeray, Charles Dickens, Alfred Tennyson, Henry Irving, Thomas Hughes MP, Lewis Carroll who photographed the house, visiting musicians Clara Schuman, violinist Joseph Joachim, his wife soprano Amalie, neighbours Marie Spartali the artists and Jeanie Senior who became the first woman civil servant. Senior was a beautiful singer and I expect she too would have sung at these gatherings.

The actress Ellen Terry’s recollections of Lavender Sweep suggest she was very fond of Taylor, describing how he presided over events in black silk knee breeches and velvet cutaway coat. She wrote; “Lavender Sweep was a sort of house of call for everyone of note…At Lavender Sweep, with the horse-chestnut blossoms strewing the drive and making it look like a tessellated pavement, all of us were always welcome…Such intimate friendships are seldom possible in our busy profession, and there was never another Tom Taylor in my life….The atmosphere of gaity which pervaded Lavender Sweep arose from his kindly, generous nature, which insisted that everyone could have a good time….I have already said that the Taylor’s home was one of the most softening and cultural influences of my early life…his house was a kind of mecca for pilgrims from America and from all parts of the world….. Yet all the time (he) occupied a position in the Home Office and often walked from Whitehall to Lavender Sweep when his day’s work was done….lavender is still associated in my mind with everything that is lovely and refined.”

Tom the Wandsworth Common activist

Tom supported the campaign to preserve Wandsworth Common from further erosion which was admirably led by John Buckmaster. Tom’s name along with other local worthies was on a poster seeking funds for its preservation from the landowner Earl Spencer. He wrote a lengthy poem in Punch entitled Warning of Wandsworth Common and another called The Commons to the Rescue aimed at the Earl.

The Battersea Society plaque at 84 Lavender Sweep on Saturday 28th September at 2pm will be unveiled by Lord Fred Ponsonby and actor Alun Armstrong and in attendance will be descendants of Tom and Laura including, I hope, Dr Peter Helps who will be celebrating his 103rd birthday on that day. There will be street theatre as there will be readings and Laura’s music played by members of the family. All welcome. Click here for more information.