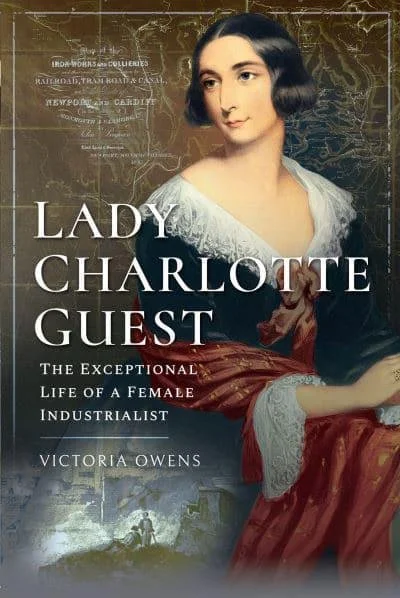

Battersea’s Reach: How One Extraordinary Woman Fell in Love with our Finest Product

By Sue Demont

You may be wondering why a blog featuring Lady Charlotte Guest of the Manor of Canford, Dorset should pop up on the Battersea Society’s heritage pages… but this was one of those serendipitous links that make the historian’s role such a joy. There was I, happily reading a biography of the remarkable Lady Charlotte because I was interested in her life and work at the Dowlais Ironworks in South Wales, when out of the page jumped the word Battersea. Lots of times! A quick cross-reference with Jeanne Rathbone’s excellent recent piece for the Nine Elms display boards and hey presto – I realised that my Charlotte Guest was one and the same as Jeanne’s Charlotte Schreiber. As they say today…who knew??

Charlotte Bertie, daughter of the ninth Earl Lindsey, was born in 1812 and went on to outlive two husbands before dying at the venerable age of 82. Aged 21 she married the iron master John Josiah Guest and went on to have ten children before his death in 1852. Such facts were unremarkable amongst the aristocracy of the mid-19th century, but from an early age it became clear that Charlotte would not grow up content to be either a society belle or a devoted matriarch, though her life encompassed aspects of both roles.

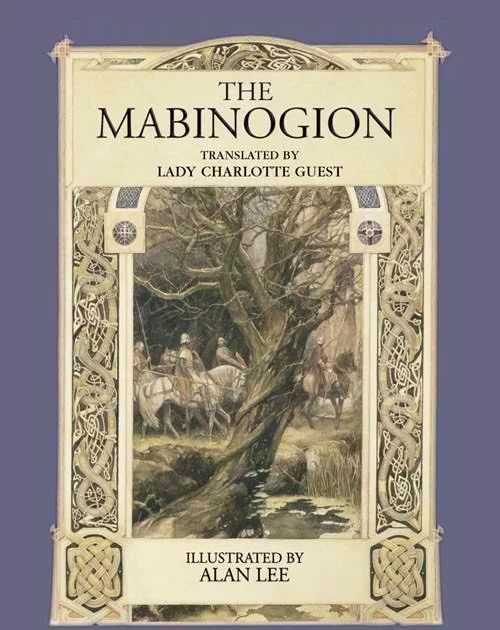

Charlotte has been variously described as a translator, a political activist, a businesswoman, an educator and a collector; in between giving birth she translated a famous set of Welsh Medieval legends (the Mabinogion) into English, campaigned for her husband in successive general elections and assisted in his running of the Dowlais ironworks which she regularly visited, hitching up her dresses in order to descend to the coal and ironstone workings many feet underground.

But at the same time, Lady Charlotte was very much the aristocrat, with a taste for the finer things of life. Presented at court in 1831, she was soon caught up in the world of high society, attending and hosting parties and balls. Although she frequently disdained such pursuits, describing them as tedious compared with the drama of life beside the ironworks, it was the world into which she was born. To the residents of Canford in Dorset she was Lady of the Manor, although she continued to take a strong interest in the ironworks until well after her husband’s death.

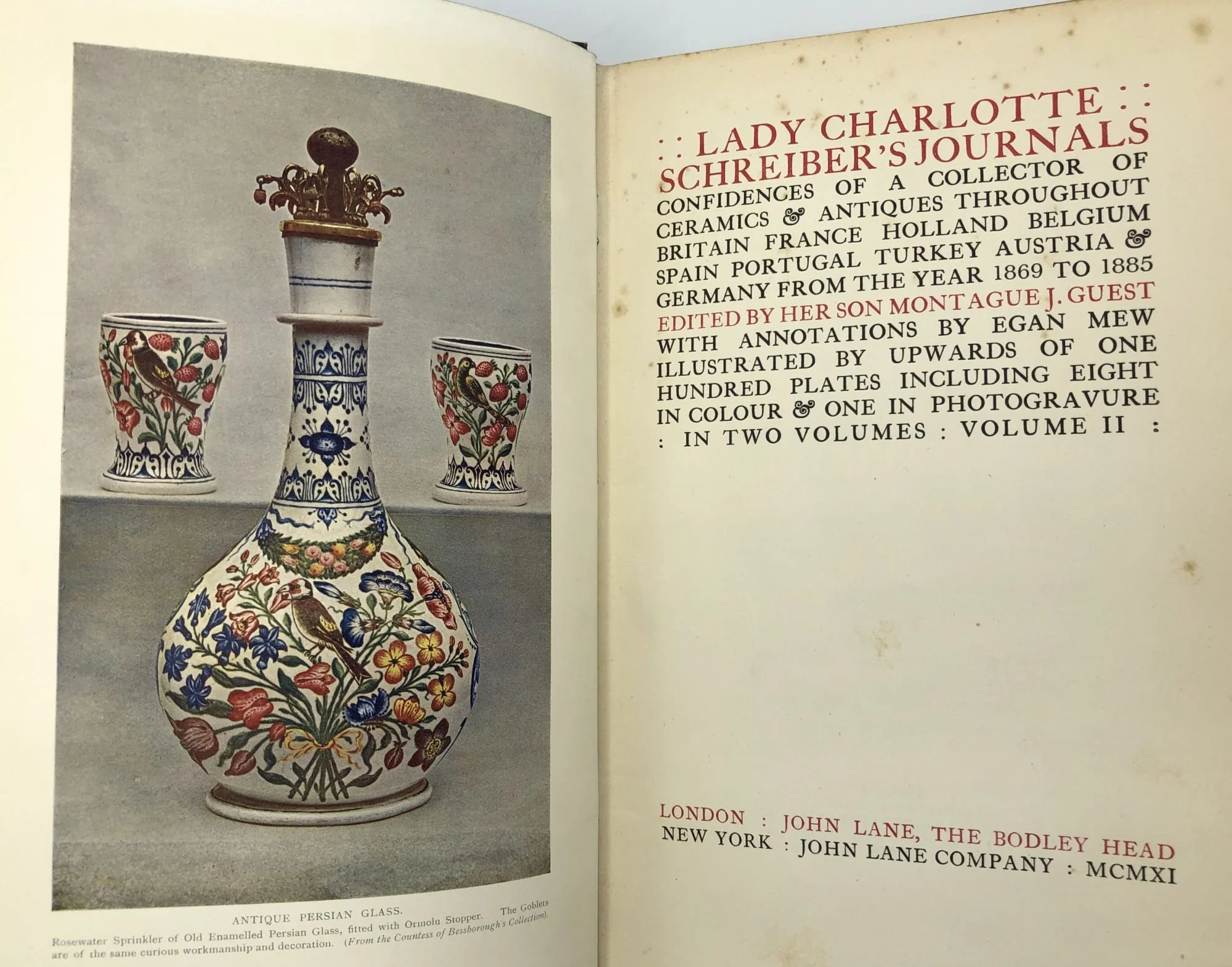

Charlotte observed the expected period of mourning, but within three years she had discarded her widow’s weeds in order to marry her son Ivor’s tutor, Charles Schreiber, who was, controversially, fourteen years younger than her. The couple soon discovered a mutual interest in collecting ceramics and other objets d’art. And Charlotte developed a particular penchant for Battersea Enamels.

The firm was established at Battersea Reach by former Lord Mayor of London Stephen Jansson, who commissioned innovative artists and craftsmen including Simon Ravenet, who engraved part of the ‘Marriage à-la-mode series’ for Hogarth in the 1740s. Battersea Enamels specialised in small luxury items popular in the 18th century - snuff-boxes, watch- and toothpick cases, coat buttons and miniature paintings - moulded from thin copper and applied with a white vitreous coating, which when fired gave the appearance of porcelain. Fine-quality engraved illustrations, usually of royal portraits or picturesque scenes, were then inked on to paper and transferred to the items by a special process, then fixed by further firing. Additional details in enamel colour were applied by brush.

Battersea Enamels rapidly became an iconic, internationally recognised brand despite operating for only three years (1753-6) on their original site. Lady Charlotte (now Schreiber) became a leading connoisseur; a recent book on enamel boxes described her as the ‘doyenne’ of English collectors of 18th century objets d’art. Her collection included many types of Battersea Enamels such as wine labels, sacred plaques and snuff boxes. Much collecting was undertaken overseas; in Utrecht one day Charlotte spent £35 (over £12,000 in today’s money) on various Battersea Enamel products. On another trip she purchased a Battersea painted plaque of a Greek myth in Rennes. By the time she donated her collection to the V&A she had recorded within it 25 different types of Battersea Enamel, though a later collector believed some of the pieces she had bought in Paris to be wrongly attributed.

By 1882 Charlotte had made her last journey overseas for collecting purposes and was cataloguing her collections for donation, but she could still succumb to temptation if an artefact was sufficiently alluring. She could not resist a £400 Battersea Enamel tea caddy, noting in her diary ‘how prices have changed since we used to buy these things’ – a clear indicator of the enduring value of Battersea’s finest product.

In her final years Charlotte could barely see, yet her passion for Battersea Enamels remained undiminished. One of her grandsons recalled how she could identify and describe a Battersea Enamel just from its feel. Today the Schreiber collection of English ceramics at the V&A is one of the largest and most important of its kind.

With thanks to Jeanne Rathbone. Click here to read Jeanne’s article on Battersea Enamels.

Example of a Battersea Enamel snuff box

Journal of a collector